I came across a blog recently that just baffles me (ironically the same day that I came across this blog of surprising responses defending women who have remained virgins). Call me the pious religious leader, I get it. And those who knew me when I was a hormone driven teenager will probably stamp the word "hypocrite" upon my face. I get that too (although it kinda supposes one can never change their mind).

But I felt I wanted to respond to this. It was so outrageous my first thought was this cannot be real. The blog outlines why one should sleep with a man on their first date. And it outlines the reasons. It boils down to this: time and good sex. But we'll look at each one individually. Then in the spirit of the other blog I read, we'll offer some responses.

First let's start with the initial claim that kind of preluded this: I’m here to tell you to ignore what everyone says and go ahead and bang him on the first date. How do I know? Well, nearly all my long-term relationships have stemmed from giving it up on date one – including my now husband.

So when I say that my long term relationships, including my wife, did not involve giving it up on the first date does that automatically negate the whole thing, since the whole bit of advice is built upon that history? No, but it begins to show also a problem in the logic here. Listen to me because this is what I did. Well, for one, guys like me can say it ain't the only way to have a lasting relationship. But likewise, we should ask ourselves if giving it up on the first date is what made those relationships last. I'm not sure I'd say her arguments make that case, but you judge for yourself.

Sexually Compatible

Here now she claims that a good lay is hard to find. Let's pause for a moment. First off, this is actually one of the problems that promiscuity proposes to relationships, it encourages creating hierarchical relationships. This is one of the gifts of sexually waiting towards marriage, it prevents one from making their sexual encounters into a "how do I rank with the next person". And let's be frank, men don't enjoy that. Think of every movie/show where a man sleeps with a woman who he knows has had sex before (and especially if he hasn't or clearly has had less), there is this constant wondering "how did I do?" How did I rate? It comes off as funny on tv, but no man really wants to have to worry and ask that question. Bottom line, one partner may not guarantee it is great, but it cuts comparisons right from it.

Here's the other issue, the claim she makes is particularly that this will let you know if they are into any weird fetishes that you should avoid immediately. But the hard truth is it assumes all weird fetishes will be learned on the first lay. While I suppose you could claim they might, the likelihood is hardly in your favor, especially if the fetish is in any way abnormal. As I recently discussed in a different post about not being good enough, relationships are a prime place where we cover up for some time our "imperfections" out of fear of being judged not good enough. Going into sex the first date guarantees you'll learn their sexual imperfections about as much as going to dinner the first date will reveal all their sloppy eating habits.

One more thought here: to judge sexual compatibility on one night is also foolish. As if things don't fire on all cylinders you should move on to find someone else, don't waste your time there. Here we come back to the time issue, but you probably are wasting more time and may be having more bad sexual encounters by constantly trying out a guy and moving on to the next instead of trying to teach one, or come to learn each other better to have a good sexual partner. It's also a rather selfish approach, that minimizes sex to simply being ultimately about how much it will please me (and here doing so in terms of instant gratification).

A side note, her final comment in this section about how a bad date but good lay becomes an instant "f*ck-buddy" also undermines for me that first argument which is this is advice that will help you create a long, lasting relationship like she has with her husband. If you want that, you don't need f*ck-buddies. You shouldn't even want them. But the construction of that scenario is "if you know from the date itself that you two aren't a good match, try him out anyways" which encourages then sleeping around not even in the pursuit of creating lasting relationships.

Penis Size

The heart of this argument is "your thinking about his penis anyways" and "don't find out you've invested all this time in a little penis". First off, let me simply put it this way, if I reversed this argument about a woman's body, I think the outcry from women would by and large be pretty unanimous. We would say nothing is more chauvinistic and insensitive than to say "gotta see her naked right away so I know if I'm wasting my time going on dates." That pretty much objectifies the other in the relationship. And it suggests that penis size matters most. She gives the example of finding out you forwent hanging out in the Hamptons with your girlfriends only to discover you're dating an uncircumcised guy or some other issue with his penis that you find less appealing. As if the rest of the time spent together is all for nothing when the penis comes out and doesn't meet your standard.

We shouldn't reduce the heart of our encounters down to the shape of a person's body. That is the kind of culture that fuels unhealthy habits and poor self-esteem in this world. It acts like if you fell in love with someone, went on marvelous dates, was well cared for, built up great memories somehow this disappointment would render all that nothing more than a waste of time. A missed opportunity in the Hamptons. For how much people long for true love, if you feel the need to put this first, and judge on that whether or not to proceed, how many good relationships are actually passed up and laid to waste by this theory. Again, doesn't to me seem a philosophy that fosters long lasting relationships. More by the ones it passes up, the things it reduces in meaning than by the value of the act of sleeping together itself.

Oh yeah, another side note, you don't have to sleep together to learn this. If Penis size really mattered that much, it does not mean one has to go all the way to sleeping with them. Your eyes work just fine without direct physical contact. Just saying.

Avoids Awkwardness

How? By having awkward sexual encounter right off the bat! The idea is this: it eliminates sexual tension or the need to pretty oneself up. She writes:

If you bang him on the first date, you don’t really need to worry so much about the impression you’re giving off on the second date – feel free to show up in yoga pants and a tank top because – guess what? He’s already seen you naked!

There are several issues here: the first is it assumes there will be a second date. This whole process from her perspective is weeding out those you find unacceptable. And so here is the real problem, you have to pass the "test" before there is any trust. Trust here is built on passing the "sexually acceptable" test, instead of trust negating the test itself. The blog of mine on not being good enough (linked above) focuses at length at how without trust we don't feel comfortable being who we are. Here the idea is to replace trust with performance. Call me skeptical as to how successful that is. What she never discusses here is also if you don't pass the test. Basing the future of the entire relationship on bodies and sexual performance puts you as much as the man on the line immediately, it makes you have to break the tension by performance instead of love and trust.

Here's the other thing. Like with the last part, it assumes that having sex is necessary to break the cycle of tension. Particularly because she identifies it as sexual tension. But let's examine that. For one, her claim "he's already seen you naked" again does not require sex. But more than that, we shouldn't have to feel afraid to be who we are anyways. The thought that you have to sleep with a man to finally be able to be in yoga pants and a tank top in front of him is appalling. Is there no self confidence to simply do that anyways? The same kind of boldness or self-confidence it takes to sleep together, could simply be applied to how you dress for a date or what you talk about. If you are willing to sleep with the person, you have enough confidence in your body with them to be able to dress that way even if you don't sleep with them. And frankly, if you are afraid of being rejected by how you look, I'd be much more wanting that rejection to come to light because of something I wore, not when I get naked with them and sleep with them.

Investment of time

It is sad that we nickle and dime our time so much that we would cut straight to the intimacy just to see if it is worth going on. As I mentioned before this method may not be a time saver. It's like bargain shopping by driving from store to store to find the best deal, saving $0.30 in the end while spending $15.00 on gas going from store to store. If you are quick to end each relationship, especially on the grounds of a single sexual relationship you may take more time finding that partner. Yes the lay may be better quicker, but how many years alone or with multiple sexual partners did it take to find one because you didn't want to get invested in time and a relationship only to have to start over later because the sex just wasn't good enough?

You may be busy, but your romantic life and possible future family (as a pastor once told a younger me "every date is a potential mate") is worth investing your time. As a pastor one thing we know is this: at the end of life people aren't lamenting that they didn't spend enough time at work or cleaning or internet surfing or whatever else is so busy that it is standing out more than your family and relationships. Those are what people lament. And truth is even though I am happily married, I don't lament my previous serious relationships as a waste of time. The time we had together created many fond memories, strong feelings, and helped form me into the man I am.

My Conclusion

Resist the culture of instant gratification and objectification. If you are apprehensive around a date, or afraid they are, sex is neither the necessary solution or necessarily a successful one. Relationships, even the ones that don't prove to be the one are not a waste of time. And it didn't take sex on the first date to find the one. And what it did take, well that was well worth it.

Covering scripture, theology, sports, movies, and the random musings of a young armchair theologian.

Thursday, April 24, 2014

My Shittiest Post Ever

Forgive the language, I know many are not comfortable with it, but this blog is in part about putting comfort or convention aside and so allow me this time to be blunt enough to use language vulgar enough to speak of what I mean.

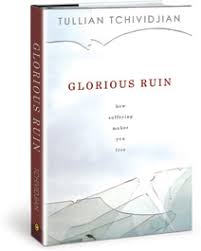

I'm currently reading Tullian Tchividjian's book Glorious Ruin: how suffering sets you free. It's an excellent one too, one I would highly recommend. A vast majority of the book is about debunking theology of glory in relation to suffering. Tchividjian gets to examining various forms of theology be it moralism or prosperity gospel and cultural trends that all are about the same thing: the avoidance of suffering.

I'm currently reading Tullian Tchividjian's book Glorious Ruin: how suffering sets you free. It's an excellent one too, one I would highly recommend. A vast majority of the book is about debunking theology of glory in relation to suffering. Tchividjian gets to examining various forms of theology be it moralism or prosperity gospel and cultural trends that all are about the same thing: the avoidance of suffering.

We can understand why. Suffering is bad. Plain and simple. No one wants to suffer. At the beginning of Part II "Confronting Suffering" is a quote by Kierkegaard, "Many and various are the things to which a man may feel himself drawn, but one thing there is to which no man ever felt himself drawn in any way, that is, to suffering and humiliation." How true. The problem, as he poses right at the outset of the book is this: we do suffer! We may avoid it, we may do all we can to get out of it, but in the end it happens. Maybe to varying degrees, but one need not make a hierarchy of suffering (which he in fact argues is a form of avoiding or dismissing just how bad it is, "well it could be worse").

The problem with a world that avoids suffering then is it doesn't always know what to do with it. And the same goes for the church. As I read it I couldn't help but think how easily we can get right in line with the culture that avoids it, for ourselves and others. The two key ways is moralization and minimization.

Moralization says I can get something out of suffering that will either free me from it or make it less miserable. You just have to figure out "why" you are suffering. Once you find the why, you can get out. Be it a specific sin that must be underlying the suffering or a lesson that will make you strong enough to overcome the suffering, this becomes the mode. Make meaning for your suffering. You can see how the church becomes a culprit here: find a way to get God's favor/blessing, get rid of whatever sin is behind this, it is a test of faith, believe more to get out of this. To one degree or another it boils down to name it and claim it. The church/God/faith/law [insert whatever you'd like will get you what you need to get out of this, you just have to get church/God/faith/law [insert whatever other self help] rightly or enough.

Minimization is the practice of avoiding it by various forms of dismissing what it actually is to suffer. Though both exist throughout the Church, I might say moralization is more common in evangelical circles while minimization is more common in mainline churches. We have our token sayings, quick words of sorry or "I'm praying for you" (though I'm not always sure how honest that phrase is) as if that makes it all better or settles it. What Tchividjian noted that particularly struck a blow to me and some of my tendencies was to find one ounce of "good" or "improvement" and latch onto that. Doing a little better? Great to hear! Nevermind that life still sucks, you're doing better! Our positivism or rather fear and avoidance of the negativeness of suffering can make us look for some way to bring the atmosphere and conversation out of it. I'm not saying it's bad to notice good parts of life, but that it is bad to avoid the rough parts because of the good ones. But that too often is our practice.

This is in part why: that's what I've culturally been trained and to what I am naturally inclined. Even after years of work in chaplaincy, it still is a habit. I confess it. I'm willing to ask and search for the crud and difficulty more now, but it still is not easy to remain there, to feel like the conversation is trapped there.

But it is, because we are. Instead of trying to cheer up and get over our problems, it's time to let our shit be shit. Instead of trying to avoid it, or steer away from it, let us be trapped there. We don't need to get out of it to be Christians. And sometimes we simply can't get out of it. That is the great power of the story, Jesus enters into suffering. God doesn't need to be only associated with the good moments and "blessings" but instead we can associate God with the shit. Not the way it normally happens, which is either God gives you what you need to escape the shit (moralism) or even more than that God must be causing the shit because he's mad at you. The death of Jesus assures us of that. It seals God's love, grace, and forgiveness so whenever we look for God in our shitholes we don't need to look for him as causing it, or him as absent from it, but him as coming among those who are trapped in a world of shit (which is the existential way of saying we are captive to sin and cannot free ourselves).

What about setting the captives free? The big lie is that freedom involves picking yourself up. As if once you convert, or have more faith, or unlock that great meaning to all this shit you will get out of it. Paul was free even though he suffered greatly in his ministry. He was free enough to die. Suffering still came upon him, but suffering could not separate him from the love and peace that is in Christ Jesus. There is talk about the ending of suffering, but that promise is given eschatalogically. Instead of the bible focusing on faith freeing you from suffering it seems more concerned with faith enduring during suffering. "The righteous shall live by faith" is one of my most favorite promises of scripture. It is given in Habakkuk where the prophet is asking God "Why are you silent while the wicked swallow up those more righteous than themselves?" (i.e. why do you let the evil prosper and the good to suffer, at their hands no less!). The promise he gives is not that karma will catch up and right the ship, the promise is not that the suffering will go away or even be lessened, merely that the righteous will live by faith. Suffering befalls them all. Death, he says, "takes captive all the peoples", the answer is not why will some escape it, but how to live in it. And that is by faith.

This means faith is not impossible while we suffer. Nor is it about avoiding suffering. It is a gift for us who suffer. Instead of looking for how people are getting out of suffering, we need to (I need to) focus on how we can have faith during suffering. And that looks to Jesus, where we know God is revealed - and not revealed apart from suffering but in the midst of it. When we are captive to suffering, when life is just shitty, instead of needing to get out of it, what we need we have, and that is God - fully and completely.

Why does that matter? If God is not a tool to less pain why does it matter? When we've been taught to look at God with a consumerist faith that looks only to what God has to sell that is appealing and good this question pops up. And when life is going shitty and all our whole nature wants is to be free of it, why does it matter if faith can't get me out of it? Here's why it matters: first because of that promise we heard - the righteous live by faith. We don't need to escape suffering in our lives to live. Getting to the good of life is more attractive, but faith says God's strength is made perfect in weakness. God matters. If we buy into God being a way out of suffering the real problem then is in suffering which we couldn't avoid or get out of we are forced to say something must be between me and God, for he is not taking me out of suffering. To find Jesus in suffering, to find faith in it, with nothing other than life itself, even there, frees us from that conclusion. It frees us from that fear. It lets us live in reconciliation. Peace with God.

Here's the other part, because a model of avoidance of suffering leads to avoidance of the gospel. Just as we are unwilling to admit we cannot escape suffering, it is a testament to how hard it truly is to admit that we cannot escape a world of sin and shame. Total and continued dependence on God during the ongoing struggle of life is what we are talking about. But often the forgiveness of sins is just as easily a pull me up out of the difficulty of sin so I can go back about the good of my life. Same with the model that wants to be totally free of suffering. Pick me up out of suffering so I can go to the good things in my life. But the totality of the good, is the good produced by faith in Christ. It is the good of Christ. To experience this goodness, we need only Jesus. If the goodness of God depends on how good you are making your life, it is not the goodness of the gospel. The goodness is always ours in Christ, no matter how bad or sucky life becomes. It doesn't make the shit go away it simply brings something into our shit - God.

We need to let ourselves truly admit to things in our life that suck. We need to call shit "shit". The value, place, faithfulness, and holiness of our life is not determined by if I overcame depression. It's no wonder the church is markedly bad at dealing with chronic illness as I noted in a previous blog. What we need to do is be willing to proclaim Christ in the shit instead calling people out of the shit to have Christ or avoiding the shit to make it seem better than it is. We need to say we are in need of a Savior. Not to evade or avoid, but to live. Now the danger is how easily the gospel can be used to minimize the suffering. This happens if we speak these promises so as to move out of engaging the suffering itself. "Don't cry, you still have Jesus" sort of thing. No, let us not use the gospel to move the conversation out of suffering but to let us confess it more. Be with each other in our suffering more. Be stuck waist deep in shit. Christ did not minimize suffering, he faced it head on, he went all the way. And so we shall not underestimate the power and hold this has on our lives, for it cost Christ his very life.

We need to let ourselves truly admit to things in our life that suck. We need to call shit "shit". The value, place, faithfulness, and holiness of our life is not determined by if I overcame depression. It's no wonder the church is markedly bad at dealing with chronic illness as I noted in a previous blog. What we need to do is be willing to proclaim Christ in the shit instead calling people out of the shit to have Christ or avoiding the shit to make it seem better than it is. We need to say we are in need of a Savior. Not to evade or avoid, but to live. Now the danger is how easily the gospel can be used to minimize the suffering. This happens if we speak these promises so as to move out of engaging the suffering itself. "Don't cry, you still have Jesus" sort of thing. No, let us not use the gospel to move the conversation out of suffering but to let us confess it more. Be with each other in our suffering more. Be stuck waist deep in shit. Christ did not minimize suffering, he faced it head on, he went all the way. And so we shall not underestimate the power and hold this has on our lives, for it cost Christ his very life.

Instead, instead I hope (and I hope you hope with me), that I, we, the church, would say that if death has lost it's sting, let's be willing to be stung. If Christ is really there, then let's not be afraid to be there too. If the goodness of the gospel is never measured by the good we make of our lives, then let's hear it as ours no matter where our lives are. Usually we feel the life we need is the one found outside of suffering, but the righteous live by faith. Life is found in Christ. That means the life we need is lived by faith in Christ. Are we, the church, willing to trust in that enough to face lives filled with suffering, and live in Christ there too?

We can understand why. Suffering is bad. Plain and simple. No one wants to suffer. At the beginning of Part II "Confronting Suffering" is a quote by Kierkegaard, "Many and various are the things to which a man may feel himself drawn, but one thing there is to which no man ever felt himself drawn in any way, that is, to suffering and humiliation." How true. The problem, as he poses right at the outset of the book is this: we do suffer! We may avoid it, we may do all we can to get out of it, but in the end it happens. Maybe to varying degrees, but one need not make a hierarchy of suffering (which he in fact argues is a form of avoiding or dismissing just how bad it is, "well it could be worse").

The problem with a world that avoids suffering then is it doesn't always know what to do with it. And the same goes for the church. As I read it I couldn't help but think how easily we can get right in line with the culture that avoids it, for ourselves and others. The two key ways is moralization and minimization.

Moralization says I can get something out of suffering that will either free me from it or make it less miserable. You just have to figure out "why" you are suffering. Once you find the why, you can get out. Be it a specific sin that must be underlying the suffering or a lesson that will make you strong enough to overcome the suffering, this becomes the mode. Make meaning for your suffering. You can see how the church becomes a culprit here: find a way to get God's favor/blessing, get rid of whatever sin is behind this, it is a test of faith, believe more to get out of this. To one degree or another it boils down to name it and claim it. The church/God/faith/law [insert whatever you'd like will get you what you need to get out of this, you just have to get church/God/faith/law [insert whatever other self help] rightly or enough.

Minimization is the practice of avoiding it by various forms of dismissing what it actually is to suffer. Though both exist throughout the Church, I might say moralization is more common in evangelical circles while minimization is more common in mainline churches. We have our token sayings, quick words of sorry or "I'm praying for you" (though I'm not always sure how honest that phrase is) as if that makes it all better or settles it. What Tchividjian noted that particularly struck a blow to me and some of my tendencies was to find one ounce of "good" or "improvement" and latch onto that. Doing a little better? Great to hear! Nevermind that life still sucks, you're doing better! Our positivism or rather fear and avoidance of the negativeness of suffering can make us look for some way to bring the atmosphere and conversation out of it. I'm not saying it's bad to notice good parts of life, but that it is bad to avoid the rough parts because of the good ones. But that too often is our practice.

This is in part why: that's what I've culturally been trained and to what I am naturally inclined. Even after years of work in chaplaincy, it still is a habit. I confess it. I'm willing to ask and search for the crud and difficulty more now, but it still is not easy to remain there, to feel like the conversation is trapped there.

But it is, because we are. Instead of trying to cheer up and get over our problems, it's time to let our shit be shit. Instead of trying to avoid it, or steer away from it, let us be trapped there. We don't need to get out of it to be Christians. And sometimes we simply can't get out of it. That is the great power of the story, Jesus enters into suffering. God doesn't need to be only associated with the good moments and "blessings" but instead we can associate God with the shit. Not the way it normally happens, which is either God gives you what you need to escape the shit (moralism) or even more than that God must be causing the shit because he's mad at you. The death of Jesus assures us of that. It seals God's love, grace, and forgiveness so whenever we look for God in our shitholes we don't need to look for him as causing it, or him as absent from it, but him as coming among those who are trapped in a world of shit (which is the existential way of saying we are captive to sin and cannot free ourselves).

What about setting the captives free? The big lie is that freedom involves picking yourself up. As if once you convert, or have more faith, or unlock that great meaning to all this shit you will get out of it. Paul was free even though he suffered greatly in his ministry. He was free enough to die. Suffering still came upon him, but suffering could not separate him from the love and peace that is in Christ Jesus. There is talk about the ending of suffering, but that promise is given eschatalogically. Instead of the bible focusing on faith freeing you from suffering it seems more concerned with faith enduring during suffering. "The righteous shall live by faith" is one of my most favorite promises of scripture. It is given in Habakkuk where the prophet is asking God "Why are you silent while the wicked swallow up those more righteous than themselves?" (i.e. why do you let the evil prosper and the good to suffer, at their hands no less!). The promise he gives is not that karma will catch up and right the ship, the promise is not that the suffering will go away or even be lessened, merely that the righteous will live by faith. Suffering befalls them all. Death, he says, "takes captive all the peoples", the answer is not why will some escape it, but how to live in it. And that is by faith.

This means faith is not impossible while we suffer. Nor is it about avoiding suffering. It is a gift for us who suffer. Instead of looking for how people are getting out of suffering, we need to (I need to) focus on how we can have faith during suffering. And that looks to Jesus, where we know God is revealed - and not revealed apart from suffering but in the midst of it. When we are captive to suffering, when life is just shitty, instead of needing to get out of it, what we need we have, and that is God - fully and completely.

Why does that matter? If God is not a tool to less pain why does it matter? When we've been taught to look at God with a consumerist faith that looks only to what God has to sell that is appealing and good this question pops up. And when life is going shitty and all our whole nature wants is to be free of it, why does it matter if faith can't get me out of it? Here's why it matters: first because of that promise we heard - the righteous live by faith. We don't need to escape suffering in our lives to live. Getting to the good of life is more attractive, but faith says God's strength is made perfect in weakness. God matters. If we buy into God being a way out of suffering the real problem then is in suffering which we couldn't avoid or get out of we are forced to say something must be between me and God, for he is not taking me out of suffering. To find Jesus in suffering, to find faith in it, with nothing other than life itself, even there, frees us from that conclusion. It frees us from that fear. It lets us live in reconciliation. Peace with God.

Here's the other part, because a model of avoidance of suffering leads to avoidance of the gospel. Just as we are unwilling to admit we cannot escape suffering, it is a testament to how hard it truly is to admit that we cannot escape a world of sin and shame. Total and continued dependence on God during the ongoing struggle of life is what we are talking about. But often the forgiveness of sins is just as easily a pull me up out of the difficulty of sin so I can go back about the good of my life. Same with the model that wants to be totally free of suffering. Pick me up out of suffering so I can go to the good things in my life. But the totality of the good, is the good produced by faith in Christ. It is the good of Christ. To experience this goodness, we need only Jesus. If the goodness of God depends on how good you are making your life, it is not the goodness of the gospel. The goodness is always ours in Christ, no matter how bad or sucky life becomes. It doesn't make the shit go away it simply brings something into our shit - God.

Instead, instead I hope (and I hope you hope with me), that I, we, the church, would say that if death has lost it's sting, let's be willing to be stung. If Christ is really there, then let's not be afraid to be there too. If the goodness of the gospel is never measured by the good we make of our lives, then let's hear it as ours no matter where our lives are. Usually we feel the life we need is the one found outside of suffering, but the righteous live by faith. Life is found in Christ. That means the life we need is lived by faith in Christ. Are we, the church, willing to trust in that enough to face lives filled with suffering, and live in Christ there too?

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Judges 11: Holy Week

Last week I was going to write a devotion for my church website on Judges 11, what I discovered was more than I realized I would come across.

For those unfamiliar with it, Judges 11 may be one of the most tragic texts of the Bible. In fact, most people are totally unfamiliar with it. It isn't the type of story you tell in Sunday School, and most people are so turned off by it they generally avoid it altogether. Not too mention Judges simply is not the most read book of the Bible, especially for churches that utilize the Revised Common Lectionary. Ironically, the story is more well known among atheistic groups against religion. The reason being that this story is so appalling many atheists are sure that if Christians read it they would stop caring about what the Bible says.

Well I challenge that assumption. If you haven't read it I encourage you to go to the link and read it. By means of spoiler alert, the Judge (ruler) Jephthah makes a vow to God that leads to the sacrifice of his daughter.

Before I go further, I should state I am well aware that there are some modern scholars who wonder if maybe Jephthah did not sacrifice his daughter, but instead offered her as a lifelong servant of the LORD. They mainly point to the fact that the text withholds from ultimately saying he killed her, and then read in texts like Genesis 22 where a ram was a suitable sacrifice in place of Abraham's son Isaac, and simply the fact that over and over the Old Testament (especially the Deuteronomic history from which Judges is a part) detested child sacrifice and associated it with idol worship (especially with the Canaanite god Molech). I think however all that aside, the text pretty clearly indicates that she was indeed sacrificed. The last two verses of the chapter show this, first by stating that Jephthah "did with her according to the vow he had made" (which was very specific that the vow would be a sacrifice in the form of a burnt offering, see v.31) and the tradition of four days of lamenting his daughter that arose in Israel. I don't see why they would lament over a daughter not killed.

You can begin to see why this is such a troubling text. A daughter sacrificed to God? What a scandal towards our faith! This is by and large covered up so people do not get troubled by it, as they should be. The commentaries I read up on regarding this text look for a way to glean a message from it, and there probably is good reason for that, after all these texts were preserved for the people, and they likely sought to see a lesson in the story much like we do with children's fables. Of the ones I heard particularly a caution towards the seriousness of vows and not making them rashly might be the most appropriate to the earliest audiences, since the text's insistence on keeping the vow is essential to the story and his rashness or apparent surprise in what he ended up vowing is his downfall. I can totally see this story standing as a lesson in regards to our vows towards God.

But the more I wrestled and struggled and sought meaning from it, the more another story emerged. That was the story of Christ himself. In Genesis 22, the near-sacrifice of Isaac is often lifted up in regards to a Christological foreshadowing (or or is lifted up as just as troubling as the Gospel narrative and atonement theories for those who reject the sacrificial aspect of the cross as divine child-abuse, part the famous critique by feminists Brown and Parker), but perhaps the story of Judges 11 stands as a better example.

For one, and as Gerhard Forde notes this is important when considering the relationship of the Father-Son in the Gospel, the child is not being forced or tricked in this story. Genesis 22, Abraham does not inform Isaac of what he has been told to do, Isaac begins to catch on (or at least realize something is amiss, Gen 22.7) but never appears willing. In fact his father binds him and places him on the altar. This is a significant difference from the narrative of Christ in the Gospels (especially John) where it is not just the Father's will to sacrifice the Son but the Son's willingness to die. "No one takes my life from me, but I lay it down of my own accord" (John 10.18) he says, and even in his struggle to face death he prays in the garden "Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will." (Mark 14.36). Though this cup, his death, is given by his Father (John 18.11), Jesus is not ignorant to this nor is he resisting it. Jephthah's daughter likewise shares this aspect. Much as Jesus who speaks of the Father's mission for him, or how this was to fulfill scripture, all the while sharing in this intent, so the daughter too, while her death is ultimately tied to her Father's words, ascents and tells him he must fulfill his vow.

This is the next important piece, the role of promise. The sacrifice of Isaac was out of a command, and more than that, the readers are already clued in that it was a "test", hinting towards the ending where he does not need to go through with it. But neither Jephthah's daughter nor Jesus died out of anyone's command, they died out of loyalty to a promise. Jephthah promised to make a sacrifice in return for victory, God promised to restore his people, a promise that included a suffering servant. God promised Jesus. And in both stories parent and child are loyal to that promise to the most grievous point, to the point where we would all say "no, you don't have to do that." What is so tragic about these stories is the place the promise/vow has...for everyone involved! The parent and the child in both stories are committed to the end, no matter the cost.

It also speaks something about the sadness of such a commitment. The suffering of God in the death of Christ is rarely gazed upon, especially by those critical of God having any will that requires the death of his Son, but here we can see that the commitment to the promise does not negate the utter tragedy and sorrow that comes when it requires the death of a beloved and only child. God would it seem much rather have had it to where Jesus was not killed by the people (see Matthew 21.33-42) but that they finally believed his word (John 6.40). But the rejection of Jesus would not stop God from fulfilling his promise in Jesus.

Now before going further there does need to be a little caution in that God did not "kill" Jesus. But his promise did cost Jesus his life, and as we see in the prayer in the garden, God's will cannot itself be removed from the passion event. God's intent to be reconciled to his people at all costs met the people's desire to be free of God at all costs on the cross. That led to the people meeting Christ in violence, and Christ not retreating. So there is a difference, in that the text when saying Jephthah "did with her accord to the vow" likely meant he was the one to kill her. In the cross, we are speaking of God's vow being how he will overcome sin, death, and slavery in Jesus. The vow does not itself require Christ's life, we mustn't forget our part. As I learned from reading Forde, attempts to let us off the hook for the death of Christ in atonement theories are just as misled as ones that want God totally uninvolved in his death. Instead we look at what actually happened: God was forgiving people in Jesus, people didn't want it but instead reject Jesus (as they rejected prophets before him, again see Matthew 21). God didn't need Jesus to die for his vow, we did. If there is one major divergence then it is that the nature of God's promise in Jesus was at work before and without his death, but that our rejection placed the promises of God into the tragedy of Christ's death because, as I said, God would not let the cross stop him from fulfilling his promise in Jesus.

The circumstance of the story then is also notable. Jephthah was rejected by his people, and then the elders come back to him for aid. And so Jephthah sought to end the dispute between Gilead and the Ammonites through recounting the work of God. Only when that fails does he make this vow and go into battle against them. Now this is a bit more of a stretch, but isn't this in many ways the story of Christ? Jesus suffers death in the midst of God's work to save people who have rejected him. Jesus' death is the inevitable end of people not believing God's word that Christ is sharing with them (and living in regards to the history of God for them). It's a bit of a stretch, but not essential to the comparison. More of a "if we're going to use a Christological typology, lets take it to the max" kind of observation.

The heart of this is the similarity of the stories of a parent losing a child (tied to a promise), and what I think is good about it is that Judges 11 can actually teach us something about Jesus. It teaches the utter tragedy of the gospel. You read this story and it saddens or angers you. It cries of injustice and unfair. Those are feelings sometimes talked about but less felt it seems around the cross. But the cross is a scandalous and offensive affair. It really doesn't read as right. It bothers some as to how God could do that (but we must there as well as in Judges 11 remember not just the word of the father but the will of the child), and it stands as a tragedy that God's love would be best shown by its presence in loss and death. It gives different weight to the word "sacrifice" when talking about the gospel.

Perhaps what is most profound here, is we have a Good Friday without an Easter, a death without a resurrection. And because of that we cannot fool ourselves into thinking that she did not die. Last Sunday the bishop was at my church and in preaching he said "let's not kid ourselves, we all know how the story ends". Knowing the resurrection sometimes undoes even a belief or realization that Jesus actually died. But when faced with the story in Judges 11, the father's sadness, the child's death with no hope, we join in the lament. It's death more as we feel it and experience it. It's scandalous. It's real. It's unfair.

So was the cross. That day no one expected Christ to rise again. It was real, scandalous, and unfair. It grieved the Father as well. The Son was sacrificed. God's promise would not rest and neither would our rejection. And so he died. Judges 11 can teach us how to grieve that event, or at least how to see the cross the way we see other deaths. Because that is what it looked like. It is a story where we should be wanting some other way, as though to tell God and Jesus "No, you don't have to do that." While Christ, seeing what we do with the "other ways" looks to his Father and says "You must fulfill this vow. Not what I will, but your will be done."

One other nice tidbit is that this story apparently explained a tradition in ancient Israel, to lament for Jephthah's daughter for four days. We Christians have taken on a similar tradition, to spend four days each year in the cycle of Christ's passion and resurrection. From Thursday to Sunday experiencing death and life anew. May this reading help you experience all the more the depths of that story, and that death, and therefore the great difference there is in saying at last "He is Risen." Because without it, we'd bury the gospel in the Bible the same way we bury Judges 11.

For those unfamiliar with it, Judges 11 may be one of the most tragic texts of the Bible. In fact, most people are totally unfamiliar with it. It isn't the type of story you tell in Sunday School, and most people are so turned off by it they generally avoid it altogether. Not too mention Judges simply is not the most read book of the Bible, especially for churches that utilize the Revised Common Lectionary. Ironically, the story is more well known among atheistic groups against religion. The reason being that this story is so appalling many atheists are sure that if Christians read it they would stop caring about what the Bible says.

Well I challenge that assumption. If you haven't read it I encourage you to go to the link and read it. By means of spoiler alert, the Judge (ruler) Jephthah makes a vow to God that leads to the sacrifice of his daughter.

Before I go further, I should state I am well aware that there are some modern scholars who wonder if maybe Jephthah did not sacrifice his daughter, but instead offered her as a lifelong servant of the LORD. They mainly point to the fact that the text withholds from ultimately saying he killed her, and then read in texts like Genesis 22 where a ram was a suitable sacrifice in place of Abraham's son Isaac, and simply the fact that over and over the Old Testament (especially the Deuteronomic history from which Judges is a part) detested child sacrifice and associated it with idol worship (especially with the Canaanite god Molech). I think however all that aside, the text pretty clearly indicates that she was indeed sacrificed. The last two verses of the chapter show this, first by stating that Jephthah "did with her according to the vow he had made" (which was very specific that the vow would be a sacrifice in the form of a burnt offering, see v.31) and the tradition of four days of lamenting his daughter that arose in Israel. I don't see why they would lament over a daughter not killed.

You can begin to see why this is such a troubling text. A daughter sacrificed to God? What a scandal towards our faith! This is by and large covered up so people do not get troubled by it, as they should be. The commentaries I read up on regarding this text look for a way to glean a message from it, and there probably is good reason for that, after all these texts were preserved for the people, and they likely sought to see a lesson in the story much like we do with children's fables. Of the ones I heard particularly a caution towards the seriousness of vows and not making them rashly might be the most appropriate to the earliest audiences, since the text's insistence on keeping the vow is essential to the story and his rashness or apparent surprise in what he ended up vowing is his downfall. I can totally see this story standing as a lesson in regards to our vows towards God.

But the more I wrestled and struggled and sought meaning from it, the more another story emerged. That was the story of Christ himself. In Genesis 22, the near-sacrifice of Isaac is often lifted up in regards to a Christological foreshadowing (or or is lifted up as just as troubling as the Gospel narrative and atonement theories for those who reject the sacrificial aspect of the cross as divine child-abuse, part the famous critique by feminists Brown and Parker), but perhaps the story of Judges 11 stands as a better example.

For one, and as Gerhard Forde notes this is important when considering the relationship of the Father-Son in the Gospel, the child is not being forced or tricked in this story. Genesis 22, Abraham does not inform Isaac of what he has been told to do, Isaac begins to catch on (or at least realize something is amiss, Gen 22.7) but never appears willing. In fact his father binds him and places him on the altar. This is a significant difference from the narrative of Christ in the Gospels (especially John) where it is not just the Father's will to sacrifice the Son but the Son's willingness to die. "No one takes my life from me, but I lay it down of my own accord" (John 10.18) he says, and even in his struggle to face death he prays in the garden "Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will." (Mark 14.36). Though this cup, his death, is given by his Father (John 18.11), Jesus is not ignorant to this nor is he resisting it. Jephthah's daughter likewise shares this aspect. Much as Jesus who speaks of the Father's mission for him, or how this was to fulfill scripture, all the while sharing in this intent, so the daughter too, while her death is ultimately tied to her Father's words, ascents and tells him he must fulfill his vow.

This is the next important piece, the role of promise. The sacrifice of Isaac was out of a command, and more than that, the readers are already clued in that it was a "test", hinting towards the ending where he does not need to go through with it. But neither Jephthah's daughter nor Jesus died out of anyone's command, they died out of loyalty to a promise. Jephthah promised to make a sacrifice in return for victory, God promised to restore his people, a promise that included a suffering servant. God promised Jesus. And in both stories parent and child are loyal to that promise to the most grievous point, to the point where we would all say "no, you don't have to do that." What is so tragic about these stories is the place the promise/vow has...for everyone involved! The parent and the child in both stories are committed to the end, no matter the cost.

It also speaks something about the sadness of such a commitment. The suffering of God in the death of Christ is rarely gazed upon, especially by those critical of God having any will that requires the death of his Son, but here we can see that the commitment to the promise does not negate the utter tragedy and sorrow that comes when it requires the death of a beloved and only child. God would it seem much rather have had it to where Jesus was not killed by the people (see Matthew 21.33-42) but that they finally believed his word (John 6.40). But the rejection of Jesus would not stop God from fulfilling his promise in Jesus.

Now before going further there does need to be a little caution in that God did not "kill" Jesus. But his promise did cost Jesus his life, and as we see in the prayer in the garden, God's will cannot itself be removed from the passion event. God's intent to be reconciled to his people at all costs met the people's desire to be free of God at all costs on the cross. That led to the people meeting Christ in violence, and Christ not retreating. So there is a difference, in that the text when saying Jephthah "did with her accord to the vow" likely meant he was the one to kill her. In the cross, we are speaking of God's vow being how he will overcome sin, death, and slavery in Jesus. The vow does not itself require Christ's life, we mustn't forget our part. As I learned from reading Forde, attempts to let us off the hook for the death of Christ in atonement theories are just as misled as ones that want God totally uninvolved in his death. Instead we look at what actually happened: God was forgiving people in Jesus, people didn't want it but instead reject Jesus (as they rejected prophets before him, again see Matthew 21). God didn't need Jesus to die for his vow, we did. If there is one major divergence then it is that the nature of God's promise in Jesus was at work before and without his death, but that our rejection placed the promises of God into the tragedy of Christ's death because, as I said, God would not let the cross stop him from fulfilling his promise in Jesus.

The circumstance of the story then is also notable. Jephthah was rejected by his people, and then the elders come back to him for aid. And so Jephthah sought to end the dispute between Gilead and the Ammonites through recounting the work of God. Only when that fails does he make this vow and go into battle against them. Now this is a bit more of a stretch, but isn't this in many ways the story of Christ? Jesus suffers death in the midst of God's work to save people who have rejected him. Jesus' death is the inevitable end of people not believing God's word that Christ is sharing with them (and living in regards to the history of God for them). It's a bit of a stretch, but not essential to the comparison. More of a "if we're going to use a Christological typology, lets take it to the max" kind of observation.

The heart of this is the similarity of the stories of a parent losing a child (tied to a promise), and what I think is good about it is that Judges 11 can actually teach us something about Jesus. It teaches the utter tragedy of the gospel. You read this story and it saddens or angers you. It cries of injustice and unfair. Those are feelings sometimes talked about but less felt it seems around the cross. But the cross is a scandalous and offensive affair. It really doesn't read as right. It bothers some as to how God could do that (but we must there as well as in Judges 11 remember not just the word of the father but the will of the child), and it stands as a tragedy that God's love would be best shown by its presence in loss and death. It gives different weight to the word "sacrifice" when talking about the gospel.

Perhaps what is most profound here, is we have a Good Friday without an Easter, a death without a resurrection. And because of that we cannot fool ourselves into thinking that she did not die. Last Sunday the bishop was at my church and in preaching he said "let's not kid ourselves, we all know how the story ends". Knowing the resurrection sometimes undoes even a belief or realization that Jesus actually died. But when faced with the story in Judges 11, the father's sadness, the child's death with no hope, we join in the lament. It's death more as we feel it and experience it. It's scandalous. It's real. It's unfair.

So was the cross. That day no one expected Christ to rise again. It was real, scandalous, and unfair. It grieved the Father as well. The Son was sacrificed. God's promise would not rest and neither would our rejection. And so he died. Judges 11 can teach us how to grieve that event, or at least how to see the cross the way we see other deaths. Because that is what it looked like. It is a story where we should be wanting some other way, as though to tell God and Jesus "No, you don't have to do that." While Christ, seeing what we do with the "other ways" looks to his Father and says "You must fulfill this vow. Not what I will, but your will be done."

One other nice tidbit is that this story apparently explained a tradition in ancient Israel, to lament for Jephthah's daughter for four days. We Christians have taken on a similar tradition, to spend four days each year in the cycle of Christ's passion and resurrection. From Thursday to Sunday experiencing death and life anew. May this reading help you experience all the more the depths of that story, and that death, and therefore the great difference there is in saying at last "He is Risen." Because without it, we'd bury the gospel in the Bible the same way we bury Judges 11.

Friday, April 11, 2014

Not Good Enough

The following blog is a repost from my church's website. I'm kinda juggling reflecting for that site now as well as this blog. So sometimes if something is quite fitting for both I might carry it over and repost

The internet is full of random (and often pointless) lists. You know what I’m talking about; “10 Most Amazing Mix-Breed Puppies” or “Top 3 and Worse 3 Steven Seagal Movies of All Time” or “5 Reasons Gen X’ers are Leaving the Church”. And if you are like me, you enjoy reading these lists. They rarely change my life. They rarely change my mind. They rarely prompt me to act. But I enjoy reading them, and sometimes they name things I agree with but never think to name myself.

Today’s post is about one of those lists. This one was “18 Ugly Truths About Modern Dating That You Deal With”. There were a few moments where I had to nod. But then I came across number 14:

“You aren’t likely to see much of someone’s genuine, unfiltered self until you’re in an actual relationship with him or her. Generally people are scared that sincerely putting themselves out there will result in finding out that they’re too available, too anxious, too nerdy, too nice, too safe, too boring, not funny enough, not pretty enough, not some other person enough to be embraced.”

It boils down to this, we are deathly afraid in relationships of not being good enough. We hold things back out of fear that we won’t be accepted. It takes love, trust, and compassion to allow us sometimes to reveal our true colors. And even then, sometimes that does not seem enough, because we still hold that doubt.

This is true with God as well. There is a parable told by Jesus about a Pharisee and a Tax Collector (Luke 18.9-14) who have different prayers. The Pharisee prays with thanks that he is not like [insert scoundrel and sinner here], and he creates an image to support this prayer: he tells God he fasts and tithes. The tax collector beats his breast in prayer “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” The Pharisee wants to lift up whatever he can to distinguish himself before God from others, including the tax collector. The tax collector simply looked to God to have the kind of compassion, love, and trust that allows one to be honest with God.

We often don’t like to face our shortcomings in the eyes of others, and it should be no surprise how much that happens in regards to God. We can create a facade of a Christian life hoping that we look good enough, we can keep our shames, doubts, and failings hidden from our brothers and sisters. And sometimes folks avoid church altogether out of the fear of judgment. In the church, we are simply afraid of not being good enough. And so like a Pharisee we create a false image. In his book Glorious Ruin Tullian Tchividjian talks about how we create barriers to honesty. He writes, “Behind each one of these barriers to honesty is a deep-seated misconception about Christianity. Contrary to popular belief, Christianity is not about good people getting better. If anything, it is about bad people coping with their failure to be good. That is to say, Christianity concerns the gospel…the gospel is a proclamation that always addresses sinners and sufferers directly (i.e. you and me).”

Instead of expecting you to be better than you are for this whole “disciple” thing to work, the Gospel invites us to be honest the same way it happens in relationships, by at all costs convincing us that in Christ we are reconciled to God. This happens through what Luther refers to as “the happy exchange”. Jesus takes your sins, weaknesses, and failings, while sharing with you his righteousness, Sonship, and resurrection. Taking what separates and giving us the fullest communion with God. This leads to Paul to say “since we are justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have obtained access to this grace in which we stand” (Romans 5.1-2). In Christ, peace with God! In Christ, we obtain a grace in which we stand before God! We always fear what the law says: not good enough. And you can try to craft your image in the law or you can stand on a total difference ground that says: Christ is more than enough!

This is how faith in Christ fosters relationship. It takes whatever would stand between us and God and won’t let them stand as a barrier, standing in grace is standing before God without barriers. And it lets us truly approach God. The same way the timid soul opens up as it connects and trusts the love of a partner. It means our faith is always initiated by God’s love towards us and always leading us into deeper relationship with him.

But it goes further than this. The reality of dating is not only that we hold back at the start of relationships but we continue to do so as they progress. What is sad is that as we know our partner more, we know more of what they want and don’t want, and we can use that to shape in what ways are we open with them. Affairs are an extreme example, but generally speaking if we know our partner expects commitment and fidelity we are more likely to hold back those moments where we have treaded or crossed those boundaries than say being honest about our passion for Football even if the other is not a football fan, because we trust that they care enough about us that our difference won’t lead to separation. It is much harder to trust that our trespass won’t lead to separation. This is the power of the promise of the gospel, it is a promise that not only the weird things about us that make us seem not your ideal servant (kind of like Moses’ speech issues not making him an ideal prophet – Exodus 4.10) but even the trespass shall not breach the relationship established on the cross. Not only has he promised to forgive, but on the cross the trespass was turned into his means of forgiveness and reconciliation. This invites us not just at the start, but throughout this life with God, to be as open as ever, knowing that when it requires the tax collector’s cry, it will be answered with the Savior’s love.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)